This manual is a work-in-progress! Help is appreciated! See the source of this manual if you want to help. Either by sending pull requests or by filing issues with specifics of what you want to see addressed here, any missing content or just confusing bits.

– CoreDNS Authors

Table of Contents

What is CoreDNS?

CoreDNS is a DNS server. It is written in Go.

CoreDNS is different from other DNS servers, such as (all excellent) BIND, Knot, PowerDNS and Unbound (technically a resolver, but still worth a mention), because it is very flexible, and almost all functionality is outsourced into plugins.

Plugins can be stand-alone or work together to perform a “DNS function”.

So what’s a “DNS function”? For the purpose of CoreDNS, we define it as a piece of software that implements the CoreDNS Plugin API. The functionality implemented can wildly deviate. There are plugins that don’t themselves create a response, such as metrics or cache, but that add functionality. Then there are plugins that do generate a response. These can also do anything: There are plugins that communicate with Kubernetes to provide service discovery, plugins that read data from a file or a database.

There are currently about 30 plugins included in the default CoreDNS install, but there are also a whole bunch of external plugins that you can compile into CoreDNS to extend its functionality.

CoreDNS is powered by plugins.

Writing new plugins should be easy enough, but requires knowing Go and having some insight into how DNS works. CoreDNS abstracts away a lot of DNS details, so that you can just focus on writing the plugin functionality you need.

Installation

CoreDNS is written in Go, but unless you want to develop plugins or compile CoreDNS yourself, you probably don’t care. The following sections detail how you can get CoreDNS binaries or install from source.

Binaries

For every CoreDNS release, we provide pre-compiled binaries for various operating systems. For Linux, we also provide cross-compiled binaries for ARM, PowerPC and other architectures.

Docker

We push every release as Docker images as well. You can find them in the public Docker hub for the CoreDNS organization. This Docker image is basically scratch + CoreDNS + TLS certificates (for DoT, DoH, and gRPC).

Source

To compile CoreDNS, we assume you have a working Go setup. See various tutorials if you don’t have that already configured. CoreDNS is using Go modules for its dependency management.

The most current document on how to compile things is kept in the coredns source.

Testing

Once you have a coredns binary, you can use the -plugins flag to list all the compiled plugins.

Without a Corefile (See Configuration) CoreDNS will load the

whoami plugin that will respond with the IP address and port of the client. So to

test, we start CoreDNS to run on port 1053 and send it a query using dig:

$ ./coredns -dns.port=1053

.:1053

2018/02/20 10:40:44 [INFO] CoreDNS-1.0.5

2018/02/20 10:40:44 [INFO] linux/amd64, go1.10,

CoreDNS-1.0.5

linux/amd64, go1.10,

And from a different terminal window, a dig should return something similar to this:

$ dig @localhost -p 1053 a whoami.example.org

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;whoami.example.org. IN A

;; ADDITIONAL SECTION:

whoami.example.org. 0 IN AAAA ::1

_udp.whoami.example.org. 0 IN SRV 0 0 39368 .

The next section will show how to enable more interesting plugins.

Plugins

Once CoreDNS has been started and has parsed the configuration, it runs Servers. Each Server is defined by the zones it serves and on what port. Each Server has its own Plugin Chain.

When a query is being processed by CoreDNS, the following steps are performed:

-

If there are multiple Servers configured that listen on the queried port, it will check which one has the most specific zone for this query (longest suffix match). E.g. if there are two Servers, one for

example.organd one fora.example.org, and the query is forwww.a.example.org, it will be routed to the latter. -

Once a Server has been found, it will be routed through the Plugin Chain that is configured for this server. This always happens in the same order. That (static) ordering is defined in

plugin.cfg. -

Each plugin will inspect the query and determine if it should process it (some plugins allow you to filter further on the query name or other attributes). A couple of things can now happen:

- The query is processed by this plugin.

- The query is not processed by this plugin.

- The query is processed by this plugin, but half way through it decides it still wants to call the next plugin in the chain. We call this fallthrough after the keyword that enables it.

- The query is processed by this plugin, a “hint” is added and the next plugin is called. This hint provides a way to “see” the (eventual) response and act upon that.

Processing a query means a Plugin will respond to the client with a reply.

Note that a plugin is free to deviate from the above list as it wishes. Currently, all plugins that come with CoreDNS fall into one of these four groups though. Note this blog post also provides background in the query routing.

Query is Processed

The plugin processes the query. It looks up (or generates, or whatever the plugin author decided this plugin does) a response and sends it back to the client. The query processing stops here, no next plugin is called. A (simple) plugin that works like this is whoami.

Query is Not Processed

If the plugin decides it will not process a query, it simply calls the next plugin in the chain. If the last plugin in the chain decides to not process the query, CoreDNS will return SERVFAIL back to the client.

Query is Processed With Fallthrough

In this situation, a plugin handles the query, but the reply it got from its backend (i.e. maybe it

got NXDOMAIN) is such that it wants other plugins in the chain to take a look as well. If fallthrough

is provided (and enabled!), the next plugin is called. A plugin that works like this is the

hosts plugin.

First, a lookup in the host table (/etc/hosts) is attempted, if it finds an answer, it returns that.

If not, it will fallthrough to the next one in the hope that other plugins may return something to the

client.

Query is Processed With a Hint

A plugin of this kind will process a query, and will always call the next plugin. However, it provides a hint that allows it to see the response that will be written to the client. A plugin that does this is prometheus. It times the duration (among other things), but doesn’t actually do anything with the DNS request - it only passes it on and inspects some meta data on the return path.

Unregistered Plugins

There is another, special class of plugins that don’t handle any DNS data at all, but influence how CoreDNS behaves in other ways. Take for instance the bind plugin that controls to which interfaces CoreDNS should bind. The following plugins fall into this category:

- bind - as said, control to what interfaces to bind.

- root - set the root directory where CoreDNS plugins should look for files.

- health - enable HTTP health check endpoint.

- ready - support readiness reporting for a plugin.

Anatomy of Plugins

A plugin consists of a Setup, Registration, and Handler part.

The Setup parses the configuration and the Plugin’s Directives (those should be documented in the plugin’s README).

The Handler is the code that processes the query and implements all the logic.

The Registration part registers the plugin in CoreDNS - this happens when CoreDNS is compiled. All of the registered plugins can be used by a Server. The decision of which plugins are configured in each Server happens at run time and is done in CoreDNS’ configuration file, the Corefile.

Plugin Documentation

Each plugin has its own README detailing how it can be configured. This README includes examples and other bits a user should be aware of. Each of these READMEs end up on https://coredns.io/plugins, and we also compile them into manual pages.

Configuration

There are various pieces that can be configured in CoreDNS. The first is determining which

plugins you want to compile into CoreDNS. The binaries we provide have all plugins, as listed in

plugin.cfg, compiled in.

Adding or removing is easy, but requires a recompile of CoreDNS.

Thus most users use the Corefile to configure CoreDNS. When CoreDNS starts, and the -conf flag is

not given, it will look for a file named Corefile in the current directory. That file consists

of one or more Server Blocks. Each Server Block lists one or more Plugins. Those Plugins may be

further configured with Directives.

The ordering of the Plugins in the Corefile does not determine the order of the plugin chain. The

order in which the plugins are executed is determined by the ordering in plugin.cfg.

Comments in a Corefile are started with a #. The rest of the line is then considered a comment.

Environment Variables

CoreDNS supports environment variables substitution in its configuration.

They can be used anywhere in the Corefile. The syntax is {$ENV_VAR} (a more Windows-like syntax

{%ENV_VAR%} is also supported). CoreDNS substitutes the contents of the variable while parsing

the Corefile.

Importing Other Files

See the import plugin. This plugin is a bit special in that it may be used anywhere in the Corefile.

Reusable Snippets

A special case of importing files is a snippet. A snippet is defined by naming a block with

a special syntax. The name has to be put in parentheses: (name). After that, it can be included in

other parts of the configuration with the import plugin:

# define a snippet

(snip) {

prometheus

log

errors

}

. {

whoami

import snip

}

Server Blocks

Each Server Block starts with the zones the Server should be authoritative for. After the zone

name or a list of zone names (separated with spaces), a Server Block is opened with an opening brace.

A Server Block is closed with a closing brace. The following Server Block specifies a server that is

responsible for all zones below the root zone: .; basically, this server should handle every

possible query:

. {

# Plugins defined here.

}

Server blocks can optionally specify a port number to listen on. This defaults to port 53 (the standard port for DNS). Specifying a port is done by listing the port after the zone separated by a colon. This Corefile instructs CoreDNS to create a Server that listens on port 1053:

.:1053 {

# Plugins defined here.

}

Note: if you explicitly define a listening port for a Server you can’t overrule it with the

-dns.portoption.

Specifying a Server Block with a zone that is already assigned to a server and running it on the same port is an error. This Corefile will generate an error on startup:

.:1054 {

}

.:1054 {

}

Changing the second port number to 1055 makes these Server Blocks two different Servers. Note that if you use the bind plugin you can have the same zone listening on the same port, provided they are binded to different interfaces or IP addresses. The syntax used here is supported since CoreDNS 1.8.4.

.:1054 {

bind lo

whoami

}

.:1054 {

bind eth0

whoami

}

Will print something like the following on startup:

.:1054 on ::1

.:1054 on 192.168.86.22

.:1054 on 127.0.0.1

Specifying a Protocol

Currently CoreDNS accepts four different protocols: DNS, DNS over TLS (DoT), DNS over HTTP/2 (DoH) and DNS over gRPC. You can specify what a server should accept in the server configuration by prefixing a zone name with a scheme.

dns://for plain DNS (the default if no scheme is specified).tls://for DNS over TLS, see RFC 7858.https://for DNS over HTTPS, see RFC 8484.grpc://for DNS over gRPC.

Plugins

Each Server Block specifies a number of plugins that should be chained for this specific Server. In its most simple form, you can add a plugin by just using its name in a Server Block:

. {

chaos

}

The chaos plugin makes CoreDNS answer queries in the CH class - this can be useful for identifying a server. With the above configuration, CoreDNS will answer with its version when getting a request:

$ dig @localhost -p 1053 CH version.bind TXT

...

;; ANSWER SECTION:

version.bind. 0 CH TXT "CoreDNS-1.0.5"

...

Most plugins allow more configuration with Directives. In the case of the chaos

plugin we can specify a VERSION and AUTHORS as shown in its syntax:

Syntax

chaos [VERSION] [AUTHORS...]

- VERSION is the version to return. Defaults to

CoreDNS-<version>, if not set.- AUTHORS is what authors to return. Default is all folks specified in the OWNER files.

So, this adds some Directives to the chaos plugin that will make CoreDNS will respond with

CoreDNS-001 as its version:

. {

chaos CoreDNS-001 info@coredns.io

}

Other plugins with more configuration options have a Plugin Block, which, just as a Server Block, is enclosed in an opening and closing brace:

. {

plugin {

# Plugin Block

}

}

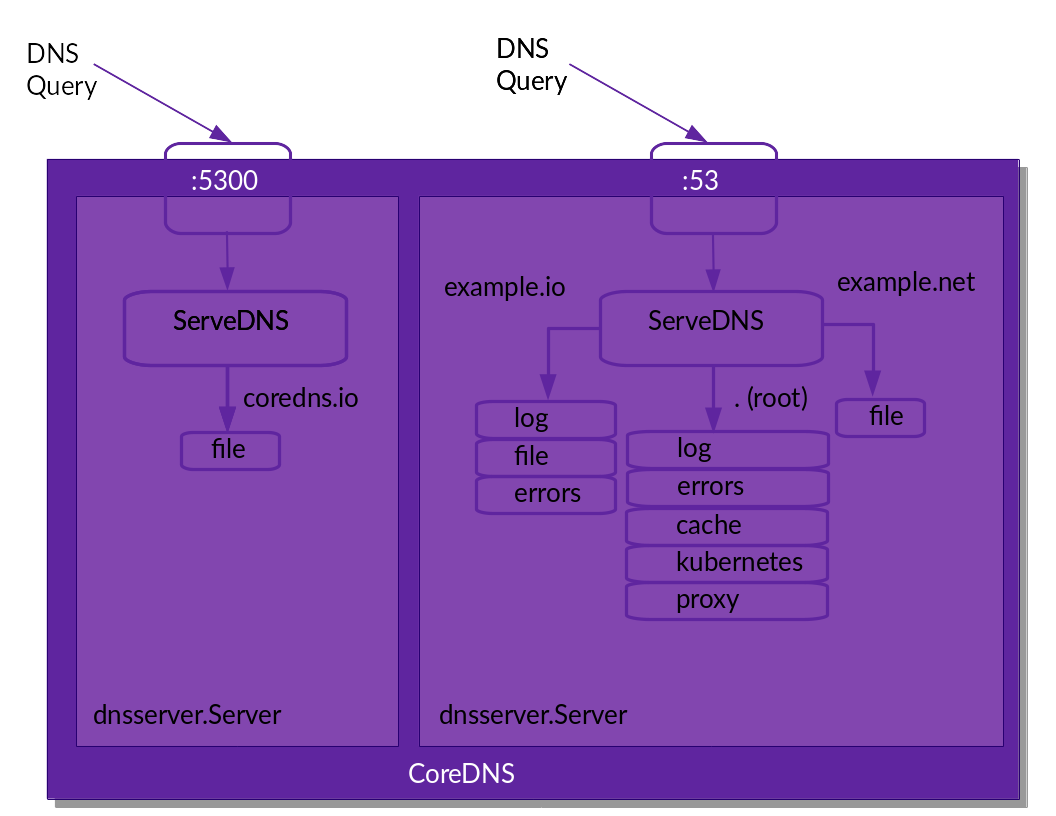

We can combine all this and have the following Corefile, which sets up 4 zones serving on two different ports:

coredns.io:5300 {

file db.coredns.io

}

example.io:53 {

log

errors

file db.example.io

}

example.net:53 {

file db.example.net

}

.:53 {

kubernetes

forward . 8.8.8.8

log

errors

cache

}

When parsed by CoreDNS, this will result in the following setup:

External Plugins

External plugins are plugins that are not compiled into the default CoreDNS. You can easily enable them, but you’ll need to compile CoreDNS your self.

Possible Errors

The health plugin’s documentation states “This plugin only needs to be enabled once”, which might lead you to think that this would be a valid Corefile:

health

. {

whoami

}

But this doesn’t work and leads to a somewhat cryptic error:

"Corefile:3 - Error during parsing: Unknown directive '.'".

What happened here? health is seen as a zone (and the start of a Server Block). The parser expects to

see plugin names (cache, etcd, etc.), but instead the next token is ., which isn’t a plugin.

The Corefile should be constructed as follows:

. {

whoami

health

}

That line in the health plugin’s documentation means that once health is specified, it is global for the entire CoreDNS process, even though you’ve only specified it for one server.

Setups

Here you can find a bunch of configurations for CoreDNS. All setups are done assuming you are not the

root user and hence can’t start listening on port 53. We will use port 1053 instead, using the

-dns.port flag. In every setup, the configuration file used is the CoreDNS’ default, named Corefile.

This means we don’t need to specify the configuration file with the -conf flag. In other words,

we start CoreDNS with ./coredns -dns.port=1053 -conf Corefile, which can be abbreviated to

./coredns -dns.port=1053.

All DNS queries will be generated with the dig

tool, the gold standard for debugging DNS. The full command line we use here is:

$ dig -p 1053 @localhost +noall +answer <name> <type>

But we shorten it in the setups below, so dig www.example.org A is really

dig -p 1053 @localhost +noall +answer www.example.org A

Authoritative Serving From Files

This setup uses the file plugin. Note the external redis plugin enables authoritative serving from a Redis Database. Let’s continue with the setup using file.

The file we create here is a DNS zone file, and it can have any name (file plugin doesn’t care). The

data we are putting in the file is for the zone example.org..

In your current directory, create a file named db.example.org and put the following contents in

it:

$ORIGIN example.org.

@ 3600 IN SOA sns.dns.icann.org. noc.dns.icann.org. (

2017042745 ; serial

7200 ; refresh (2 hours)

3600 ; retry (1 hour)

1209600 ; expire (2 weeks)

3600 ; minimum (1 hour)

)

3600 IN NS a.iana-servers.net.

3600 IN NS b.iana-servers.net.

www IN A 127.0.0.1

IN AAAA ::1

The last two lines are defining a name www.example.org. with two addresses, 127.0.0.1 and (the

IPv6) ::1.

Next, create this minimal Corefile that handles queries for this domain and adds the

log plugin to enable query logging:

example.org {

file db.example.org

log

}

Start CoreDNS and query it with dig:

$ dig www.example.org AAAA

www.example.org. 3600 IN AAAA ::1

It works. Because of the log plugin, we should also see the query being logged:

[INFO] [::1]:44390 - 63751 "AAAA IN www.example.org. udp 45 false 4096" NOERROR qr,aa,rd,ra 121 0.000106009s

The above logs show us the address CoreDNS replied from (::1) and the time and date it replied.

Furthermore, it logs the query type, the query class, the query name, the protocol used (udp), the

size in bytes of the incoming request, the DO bit state, and the advertised UDP buffer size. This is

data from the incoming query. NOERROR signals the start of the reply, which is the Response Code

sent back, followed by the set of flags on the reply: qr,aa,rd,ra, the size of the reply in bytes

(121), and the duration it took to get the reply.

Forwarding

CoreDNS can be configured to forward traffic to a recursor with the forward. Here, we will use forward and focus on the most basic setup: forwarding to Google Public DNS (8.8.8.8) and Quad9 DNS (9.9.9.9).

We don’t need to create anything except for a Corefile with the configuration we want. In this case, we want all queries hitting CoreDNS to be forward to either 8.8.8.8 or 9.9.9.9:

. {

forward . 8.8.8.8 9.9.9.9

log

}

Note that forward allows you to fine tune the names it will send upstream. Here, we

chose all names (.). For instance: forward example.com 8.8.8.8 9.9.9.9 would only forward names

within the example.com. domain.

Start CoreDNS and test it with dig:

$ dig www.example.org AAAA

www.example.org. 25837 IN AAAA 2606:2800:220:1:248:1893:25c8:194

Forwarding Domains To Different Upstreams

A common scenario you may encounter is that queries for example.org need to go to 8.8.8.8 and

the rest should be resolved via the name servers in /etc/resolv.conf. There are two ways that

could be implemented in a Corefile:

- Use multiple declarations of forward plugin within a single Server Block:

. {

forward example.org 8.8.8.8

forward . /etc/resolv.conf

log

}

- Use multiple Server Blocks, one for each of the domains you want to route on:

example.org {

forward . 8.8.8.8

log

}

. {

forward . /etc/resolv.conf

log

}

This leaves the domain routing to CoreDNS, which also handles special cases like DS queries. Having two smaller Server Blocks instead of one has no negative effects except that your Corefile will be slightly longer. Things like snippets and the import will help there.

Recursive Resolver

CoreDNS does not have a native (i.e. written in Go) recursive resolver, but there is an (external) plugin that utilizes libunbound. For this setup to work, you first have to recompile CoreDNS and enable the unbound plugin. Super quick primer here (you must have the CoreDNS source installed):

- Add

unbound:github.com/coredns/unboundtoplugin.cfg. - Do a

go generate, followed bymake.

Note: the unbound plugin needs cgo to be compiled, which also means the coredns binary is now linked against libunbound and not a static binary anymore.

Assuming this worked, you can then enable unbound with the following Corefile:

. {

unbound

cache

log

}

cache has been included, because the (internal) cache from unbound is disabled to allow the cache’s metrics to works just like normal.

Writing Plugins

As mentioned before in this manual, plugins are the thing that make CoreDNS tick. We’ve seen a bunch of configuration in the previous section, but how can you write your own plugin?

See Writing Plugins for CoreDNS for an older post on this subject. The plugin.md documented in CoreDNS’ source also has some background and talks about styling the README.md.

The canonical example plugin is the example plugin. Its github repository shows the most minimal code (with tests!) that is needed to create a plugin.

It has:

setup.goandsetup_test.go, which implement the parsing of configuration from the Corefile. The (usually named)setupfunction is called whenever the Corefile parser see the plugin’s name; in this case, “example”.example.go(usually named<plugin_name>.go), which contains logic for handling the query, andexample_test.go, which has basic units tests to check if the plugin works.- The

README.mdthat documents in a Unix manual style how this plugin can be configured. - A LICENSE file. For inclusion in CoreDNS, this needs to have an APL like license.

The code also has extensive comments; feel free to fork it and base your plugin off of it.

How Plugins Are Called

When CoreDNS wants to use a plugin it calls the method ServeDNS. ServeDNS has three parameters:

- a

context.Context; - a

dns.ResponseWriterthat is basically the client’s connection; - a

*dns.Msgthat is the request from the client.

ServeDNS returns two values: a (response) code and an error. The error is logged when the

errors is used in this server.

The code tells CoreDNS if a reply has been written by the plugin chain or not. In the latter case, CoreDNS will take care of that. For the code’s values, we reuse the DNS return codes (rcodes) from the dns package.

CoreDNS treats:

- SERVFAIL (dns.RcodeServerFailure)

- REFUSED (dns.RcodeRefused)

- FORMERR (dns.RcodeFormatError)

- NOTIMP (dns.RcodeNotImplemented)

As special and will then assume nothing has been written to the client. In all other cases, it assumes something has been written to the client (by the plugin).

See this post on how to compile CoreDNS with your plugin.

Logging From a Plugin

Use the log package to add logging to your plugin. You initialize it with:

var log = clog.NewWithPlugin("example")

Now you can log.Infof("...") to print something to standard output prefixed with level [INFO] plugin/example. Level can be: INFO, WARNING or ERROR.

In general, logging should be left to the higher layers when returning an error. However, if there is a reason to consume the error but still notify the user, then logging in the plugin can be acceptable.

Metrics

When exporting metrics, the Namespace should be plugin.Namespace (=“coredns”), and the

Subsystem should be the name of the plugin. The README.md for the plugin should then also contain

a Metrics section detailing the metrics. If the plugin supports readiness

reporting, it should also have a Ready section detailing it.

Documentation

Each plugin should have a README.md explaining what the plugin does and how it is configured. The file should have the following layout:

- Title: use the plugin’s name

- Subsection titled: “Named”

with

<plugin name> - <one line description>., i.e. NAME DASH DESCRIPTION DOT. - Subsection titled: “Description” with a longer description and all the options the plugin supports.

- Subsection titled: “Syntax” detailing syntax and supported directives.

- Subsection titled: “Examples”.

- Optional Subsection titled: “See Also”, that references external documentation, like IETF RFCs.

- Optional Subsection titled: “Bugs” that lists things that do not work yet.

More sections are, of course, possible.

Style

We use the Unix manual page style:

- The name of the plugin in the running text should be italic:

*plugin*. - All CAPITAL user supplied arguments in the running text reference use strong text:

**EXAMPLE**. - Optional text is in block quotes:

[optional]. - Use three dots to indicate multiple options are allowed:

arg.... - Item used literal:

literal.

Example Domain Names

Please be sure to use example.org or example.net in any examples and tests you provide. These

are the standard domain names created for this purpose. If you don’t, there is a chance your fantasy

domain name is registered by someone and will actually serve web content (which you may like or not).

Fallthrough

In a perfect world, the following would be true for plugins: “Either you are responsible for a zone or

not”. If the answer is “not”, the plugin should call the next plugin in the chain. If “yes” it

should handle all names that fall in this zone and the names below - i.e. it should handle the

entire domain and all sub domains, also see here

on how a query is process with fallthrough enabled.

. {

file example.org db.example

}

In this example the file plugin is handling all names below (and including) example.org. If

a query comes in that is not a subdomain (or equal to) example.org the next plugin is called.

Now, the world isn’t perfect, and there are good reasons to “fallthrough” to the next middleware, meaning a plugin is only responsible for a subset of names within the zone. The first of these to appear was the reverse plugin, now replaced with the generalized template plugin that can synthesizes various responses.

The nature of the template plugin might only deal with specified record TYPEs, and then only

for a subset of the names. Ideally, you would want to layer template in front of another

plugin such as file or auto. This means template could handle some special

reverse cases and all other requests are handled by the backing plugin. This is exactly what

“fallthrough” does. To keep things explicit we’ve opted that plugins implementing such behavior

should implement a fallthrough keyword.

The fallthrough directive should optionally accept a list of zones. Only queries for records

in one of those zones should be allowed to fallthrough.

Qualifying for main repo

See this document describing the requirements.